From tachi to katana: the heritage of ancestral Japanese blades

Forging a katana: A tradition over a thousand years old

The Japanese katana is not just a weapon; it is a cultural heritage, passed down through generations of master swordsmiths.

Since the Heian period (794–1185), Japanese swords have accompanied the evolution of the country — both on the battlefield and in the collective imagination.

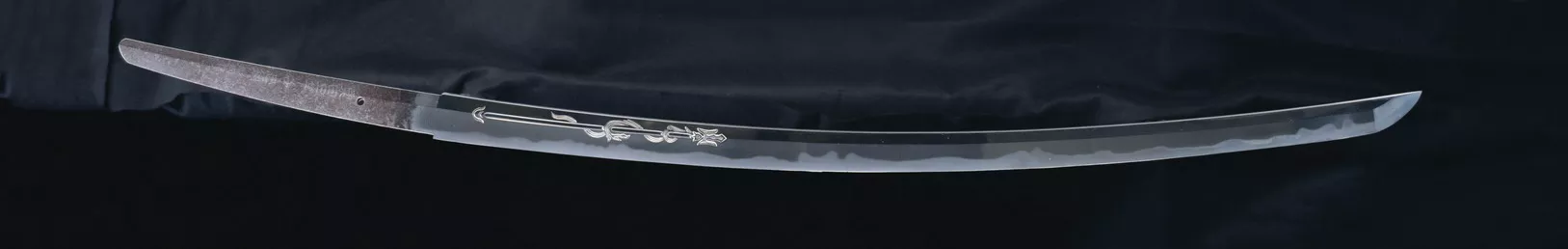

Blade forged by Ikkanshi Tadatsuna in 1709, at the end of his life. A masterpiece representing the craftsmanship of this Osaka artisan, active during the Edo period. Tadatsuna often included the inscription "forged and engraved" on his signature, marking pieces with such finely chiseled motifs. Classified as an Important Cultural Property of Japan.

The Nihonto katana

Nihonto could be translated as “ancient sword,” but it also means “sword forged in Japan.”

In fact, within the Nihonto there are the Jōkotō, Kotō, Shintō, Shinshintō, Gendaitō, Showatō, and finally the Shinsakutō or Shinken, each belonging to a different period, from the oldest to the most recent.

The Jōkotō katana

The first weapons appeared in Japan during the Yayoi period, starting around 300 B.C.

The Nihontō, or Japanese sword, was born from a desire for purely technical improvement.

However, it turns out that swords were indeed considered works of art, respected very early in Japanese history.

The first blades (Jōkotō) were also objects of worship.

Between a sword and a saber, there is a major difference (the sword has two cutting edges, while the saber has only one), and the Japanese saber or katana as we know it today had its ancestor appear in the middle of the Heian period (794–1099) with the first sabers called Jōkotō.

The first curves, however, appeared around the middle of the Asuka era (645), particularly with the swordsmith Amakuni, starting around 700 (one of the main figures in Japanese swordsmithing, creator of the tachi).

There were many types of Jōkotō: the tsurugi (jian), warabite no tashi, tosu, and especially the tachis, which are the direct ancestors of the katana.

Sword forging developed tremendously during this period. Government power diminished in favor of the clans that divided Japan.

Numerous wars broke out, which explains these technical innovations.

Although many Jōkotō of poor quality exist (probably poorly executed heating techniques and low-quality metals), there are some exceptional blades that are comparable to modern katanas.

Sword forging developed enormously during this period. Government power diminished in favor of the clans that divided Japan. Numerous wars broke out, which explains these technical innovations. Although many Jōkotō of poor quality exist (probably poorly executed heating techniques and low-quality metals), there are some exceptional blades that have nothing to envy from modern katanas.

The Kotō katana

They appeared around the second half of the Heian era, up to the Muromachi period.

These were again tachis, but this time they became increasingly curved: it was discovered that this resulted in better cutting capabilities and improved shock resistance.

Naturally, the blades curved during forging: this is a physical consequence when the cutting edge is close to the back of the blade.

The closer the edge is to the back of the blade, the sharper the weapon. Swordsmiths then decided not to avoid curves anymore, but rather to work with them.

Kiriha-zukuri designs were then replaced by Shinogi-zukuri, an evolution of the point making it steeper (or thinner) at the cutting edge and in the area just beyond.

This structure made the blade much sharper (this structure is still widely used today).

However, being sharper also made it weaker against armor: since this sharpness came from a thinner, finer edge (a steeper angle), the risk of breaking increased.

This is when the true challenge of Japanese swordsmithing appeared: achieving the right balance, making a blade that was increasingly sharp without compromising strength. Managing these angles became essential (more so than other techniques) and allowed katanas to become more flexible and therefore less prone to breaking on impact, especially with the arrival of composite techniques. It only took a few “failed” Jōkotō with unwanted curves that were poorly corrected, combined with careful observations, to realize that these curves allowed weapons to become far more effective cutting tools.

The Kotō era was born. These blades were not yet called katanas, but tachis. Their hamon (temper lines) became much more refined, their nakago (tang) better crafted, and excellent pieces became less rare: forging techniques became significantly more advanced.

The first traditions appeared with the Yamato Den school and its first branch, the Senjuin school, around 1184, inspired by the swordsmith Amakuni.

Then, in 1187, the Awataguchi school revived the techniques of Sanjo Munechika, paving the way for the Yamashiro tradition, which later led to the Bizen tradition with the Ichimonji school.

The Bizen tradition quickly became the most successful, closely followed by the Yamashiro tradition.

Some tachis were later used mainly by cavalry, with a metal scabbard and a sageo (braided cord for the scabbard), making them particularly valuable on horseback.

The blades of this period had increasingly accentuated curves. The optimal striking zone (called “mono-uchi”) was located in the first third of the blade, while the middle section of the katana’s blade was the least effective.

On average, they measured around 70 cm and at least 60 cm, making their size comparable to modern katanas.

The Uchigatana Katana

Often of rather poor quality and generally intended for lower-ranking warriors, this period marked the beginning of distinguishing between different blade sizes and assigning the common names katanas and wakizashis in everyday language.

The term Uchigatana would eventually disappear over time, giving way to these newer terms.

Their quality was often poor because the Ōnin civil war led to mass production, and renowned swordsmiths became fewer in number.

Katanas were produced in simplified Bizen and Mino traditions and were called kazu-uchi mono or tabagatana (mass-produced swords), of lower quality, distinguished from the chumon-uchi (high-quality, custom-made blades, often crafted specifically for feudal lords).

Composite forging continued to evolve with the introduction of kobuse and makuri techniques applied to katanas, creating blades made from different layers of steel to achieve a hard outer surface combined with a softer, more flexible core, allowing better shock absorption.

The Shintō Katana

Then comes the Azuchi Momoyama era.

Numerous modifications allowed craftsmanship in general to develop considerably.

The unification led to the disappearance of many traditional forging schools (the five great traditions), but great masters began to emerge across Japan.

Meanwhile, kenjutsu and the wearing of the daishō developed significantly.

We begin to see the emergence of Shintō (“new swords”), which are very different from what was previously made.

However, the quality of the steel grain in these Shintō blades is generally less fine than that of the Kotō. This is due to the massive importation of lower-quality steel from Portugal and Holland (nanbantetsu or hyotantetsu or konohatetsu, as opposed to watetsu, Japanese steel), and the use of poor-quality domestic Japanese steel from the west (steel containing too much phosphorus, increasing the risk of blade breakage).

Still, the term Shintō is justified: these new swords are undeniably superior in terms of forging techniques, which developed extensively from the end of the Muromachi period, in parallel with this rapid and massive production.

The old techniques disappeared for a time, but were gradually rediscovered, and new methods were added, giving rise to excellent-quality craftsmanship.

The Edo period, also sometimes called the Tokugawa period, saw the return of aesthetic and refined katana-making, reminiscent of the Kotō era.

The term Shintō continues to be used, even though there is a significant difference between early Shintō blades and later ones, which are generally more aesthetic and often of higher quality.

Curvature styles were redesigned to more closely resemble those of the tachi swords, and magnificent hamon (temper lines) became more developed.

The art of Shintō Tokuden emerged, a new forging style.

A distinction arose between eastern and western styles: Osaka Shintō vs. Edo Shintō.

Osaka, a city of culture, produced more sophisticated katanas, while Edo, where Bushidō was followed strictly, produced heavier and more imposing swords, where technical performance was prioritized over aesthetics.

The term wazamono is used to describe exceptionally sharp katanas, since this period was marked by cutting tests (tameshigiri), and some sword testers were officially employed by the government to conduct these tests.

If you are looking for an antique Nihonto or Shinto sword, visit our partner, the specialist at Antique Sword

If you are looking for a modern Nihonto sword, visit our website Mikazuki.fr