The Evolution of the katana:

From the Edo Period to Modern Shinsakutō

This uchigatana-type sword from the Kamakura period features a tantō-style design, forged in a larger size with a curved blade and a flat hira-zukuri structure. It is a rare piece for its time. Kuniyoshi, a swordsmith from the Awataguchi school in the Yamashiro province, is believed to have been the son of Norimune and, according to the inscription on this sword, held the title of Sahyōe no Jō of the Fujiwara clan.

The Kotō (古刀): Ancient Swords (before 1596)

Sword from the mid-Nanbokuchō period (1338 ~ 1367)

The Kotō, literally "ancient swords," refers to katanas forged before the Keichō period (1596).

Forged in a Japan still divided by incessant wars, these swords reflect an era of martial refinement where each province had its own traditions.

Numerous regional forging schools (the Gokaden) emerged during this time: Yamato, Bizen, Sōshū, Mino, and Yamashiro.

These katanas are generally short, sturdy, functional, and often marked by distinctive temper lines (hamon).

Shintō (新刀): New Swords (1596–1780)

Beginning of the Keian era: 1648 ~ 1652

With the peace established under the Tokugawa shogunate, conflicts decreased, and swordsmiths entered a period of relative stability.

The sword’s role shifted: from a pure weapon of war, it also became a symbol of social status and refinement.

The quality of steel improved, as did the decorative aspects of the swords.

This era is known as Shintō, or "new swords."

It also saw the appearance of the daishō (the katana/wakizashi pair), worn by all samurai. The katana became an essential element of the code of honor (bushidō).

Shinshintō (新々刀):

Traditional Renewal (1781–1876)

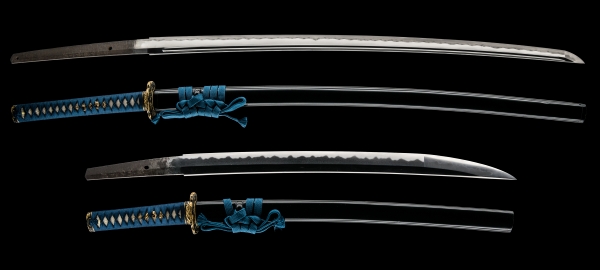

A Daishō by Koyama Munetsugu

At the end of the Edo period, the samurai gradually lost their influence in favor of merchants and an emerging urban class.

Prolonged peace and political reforms made the katana less and less useful in daily life.

It gradually fell into oblivion. However, Suishinshi Masahide, a great swordsmith and reformer, revived its prestige by restoring the katana’s noble status in the art of forging.

He trained more than a hundred students in Edo and revitalized ancient traditions, including the Gokaden styles.

During this time, tachi and even tantō blades made a comeback.

The Haitōrei Edict and the End

of the Samurai (1876)

In 1876, the Haitōrei edict officially prohibited former samurai from wearing swords in public. This decision marked a historical turning point: the katana, formerly a symbol of the warrior, became an object of art, tradition, and collection.

The Gendaitō (現代刀):

Traditional Modern Swords (1876–1945)

Antique Japanese Katana Sword by Tachibana Munehiro

Despite the prohibition, some swordsmiths continued producing blades using ancestral methods. These are called Gendaitō, or modern traditionally forged swords.

Demand drastically declined, forcing many artisans to change professions.

However, interest in sword forging was rekindled thanks to the intervention of Emperor Meiji, who was passionate about swords.

In 1906, he appointed several craftsmen as Gigei-in (技芸員), including the renowned Gassan Sadakazu and Miyamoto Kanenori, and compensated them so they could preserve the art of sword forging.

These swords retain all the nobility and rigor of past eras.

Shōwatō and Guntō:

Mass-Produced Military Swords (1931–1945)

Katana Gunto - Katana samurai

(軍刀): swords produced in series, often made from industrial steel, and sometimes decorated to symbolize courage and honor.

Several types can be distinguished:

Shin-Guntō: for the army, with a traditional mounting style.

Kai-Guntō: for the navy, often made of stainless steel.

Kyū-Guntō: models inspired by European-style handles.

Among this mass production, only certain swords — such as those forged at Yasukuni, or the models by Gassan Sadakatsu and Nobufusa — maintained a traditional level of quality. These are classified as Gendaitō, in contrast to the majority of Shōwatō, which were produced breaking away from traditional craftsmanship.

Surrender and the attempted destruction of heritage

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, the Allies ordered the confiscation and destruction of many swords, seen as symbols of Japanese militarism.

Fortunately, many pieces were saved by collectors or foreign officers who respected their cultural value.

Shinsakutō (新作刀) and Shinken:

The Contemporary Revival

Katana Shinken - Katana samurai

Today, traditional forging has not disappeared, on the contrary.

Descendants of master swordsmiths perpetuate the ancient techniques under modern conditions.

Shinsakutō swords, or “new creations,” are forged by hand according to historical methods, using Tamahagane steel, with all the ritual stages of folding, tempering, and polishing.

When they are sharp, they are also called Shinken , true functional swords used in Iaido, Kenjutsu, or in Tameshigiri (cutting tests).

The quality of certain modern pieces rivals that of the Shintō or Shinshintō periods, and some even hope one day to rediscover the perfection reached by masters like Masamune or the Ichimonji.

The art of the Japanese sword has therefore never ceased to live: it adapts, is transmitted, and continues to fascinate.

The Katana, a living heritage

From the medieval battlefield to today’s collections, the katana is much more than a weapon: it is a symbol of Japanese tradition, discipline, and elegance.

Despite wars, reforms, and upheavals, it has crossed the centuries without losing its soul.

Even today, in the hands of passionate swordsmiths, it lives, transforms, and continues to inspire lovers of history, swords, and Japanese culture.